Fight Stats Rewind: Round-by-Round Look at Hendricks vs Lawler II

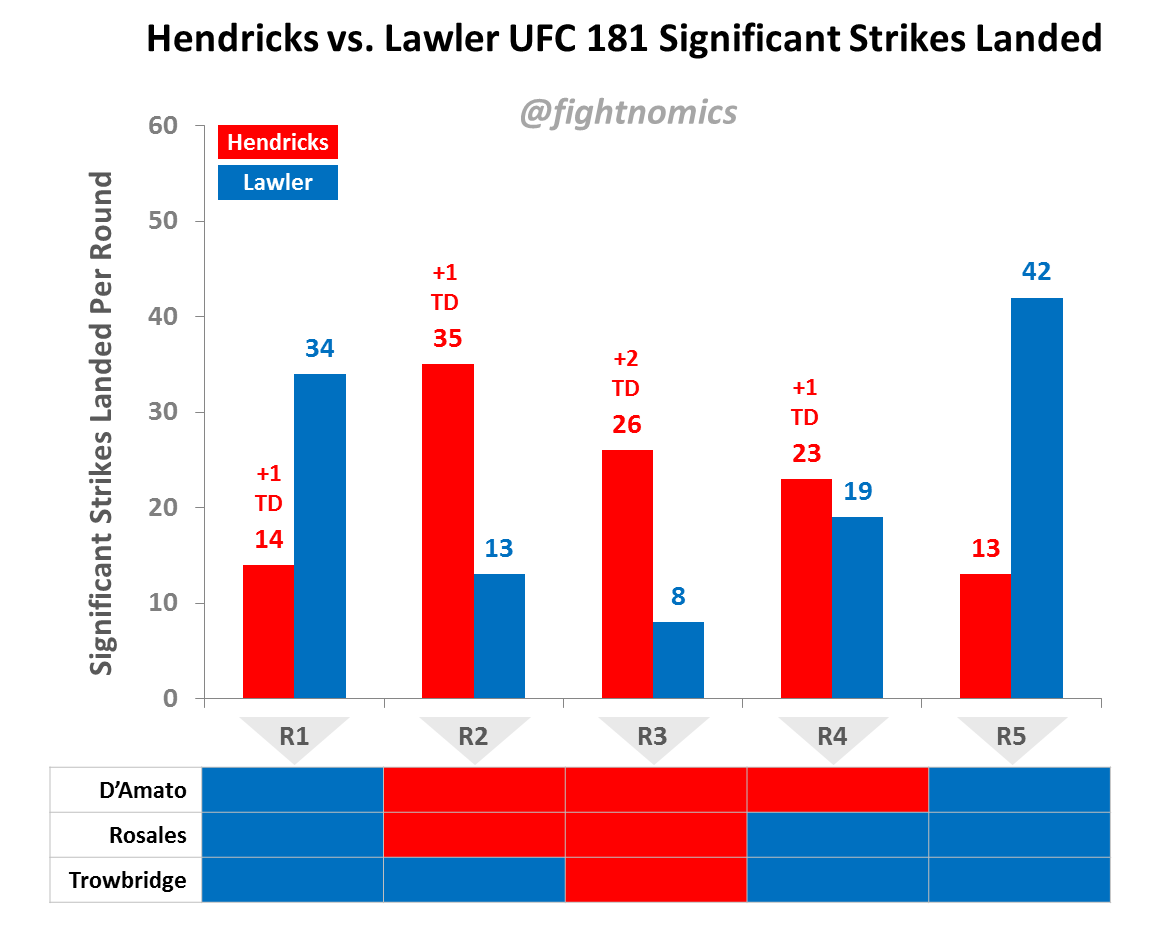

By @fightnomics In a fight that many expected to be close, Hendricks and Lawler put in another highly competitive contest in a rematch of their first title fight at UFC 171 last March. But this time at UFC 181, it was Lawler who earned the decision. But not without some controversy. It was the first time a challenger took a Split Decision victory from an incumbent champion, and when the final scores were read, reactions were strong all over. Hendricks is now 3-2 in fights ending with disputed decisions, with wins over Grant, Pierce, and Koscheck, but more recently losses to St-Pierre and now Lawler. Perhaps Hendricks’s fight IQ is to blame, or maybe it’s uninspired cornering. Or maybe we just need to realize that MMA judges are consistently inconsistent in their scoring, and that it only takes a little variance from round-by-round scores to sway the outcome of a fight. Perhaps the true cause of disagreement in the fight’s outcome is due to something much more fundamental: people value different MMA techniques very differently. Here’s how the statistics for the fight ended up, and how each judge scored the contest per round.

For more on historical judging scores, check out Chapter 12 of the “Fightnomics” book.

For more on historical judging scores, check out Chapter 12 of the “Fightnomics” book.

Based on the numbers above, Lawler was clearly the more effective fighter in the first and final rounds. But it appears that Hendricks landed more offense in rounds two through four, with the fourth round being the closest of all rounds. This led 75% of MMA media to favor Hendricks as the winner of the decision, while two of three judges gave the fight to Lawler. Cage side in the arena, judges were in perfect agreement for three out of five rounds, unanimously scoring Lawler the winner of rounds one and five, and Hendricks the winner of the third. But in rounds two and four there was disagreement over the winner. This is not uncommon, as even in three-round fights ending in decision judges will disagree with each other on at least one round more often than not. Disagreement therefore, is the norm, not the exception. So given that round four was the closest of all rounds, it’s not at all surprising that three judges couldn’t agree on the winner of that round. But by the end of round four, two judges had already picked their winner having scored one fighter with three rounds, one for Hendricks and the other for Lawler. Only Rosales had it even going into the final frame. The disagreement over round four opened the door for Lawler to steal the comeback win on Rosales’s card, while it had already sealed the victory for Lawler on the card of Trowbridge. Round four was clearly the closest round of the fight, and even the statistical advantages of Hendricks cannot guarantee awarding him the round. Hendricks outlanded Lawler by a mere four significant strikes, landed one takedown (missing two others), but was outworked by Lawler in total strikes due to Lawler being busier on the ground. It was close – very close – and judges rarely show perfect agreement when a round is that close. Hendricks technically controlled the cage and ground position, but he didn’t do anything once on the ground. And perhaps most importantly, Lawler’s aggressiveness on the ground while Hendricks simply stalled and held onto a leg was a textbook case of how to “steal” a close round at the very end. Looking closer however, the most glaring head scratcher occurred much earlier in the fight appearing on the scorecard of judge Glenn Trowbridge in the second round. In a round that was the second most lopsided of all rounds in the fight and clearly favored Hendricks from a statistical standpoint, Trowbridge declared Lawler the winner. Hendricks outlanded Lawler 35-13 on Significant Strikes, and also threw a total of 67 strikes to Lawler’s 34. Furthermore, Hendricks was one for three on takedown attempts, and also finished the round with a submission attempt that was interrupted by the buzzer. Hendricks was busier, more accurate and efficient, and appeared to win the round in all positions. So how does one judge award this round to Lawler? This is the real controversy of the Hendricks-Lawler rematch. Not the outcome of the fight, but this one score on the cards in round two. Although Hendricks finished think he won the “fight,” it’s round by round scoring that counts. And the closeness of round four and the perception that he was already starting to coast place that round squarely in the realm of judging coin-flips. The real mystery of disagreement in round two boils down to a key difference hidden within the metric of Significant Strikes. As I explain in detail in the “Fightnomics” book, not all strikes are created equal. And while leg kicks are certainly valuable, they aren’t as flashy as body or head kicks and they don’t win rounds at the same rate. By the time the fight was over, 39 of Hendricks’s Significant Strikes landed were leg kicks, more than a third of his total. Lawler attempted just one, a low kick that was checked by Hendricks in round two. The key difference between the striking styles of the two fighters reveals how different judges value different factors during a round of MMA. Judges D’Amato and Rosales saw Hendricks as the busier fighter, and the one in control of round two. But for judge Trowbridge, Lawler’s more dangerous striking full of head kicks and swing-for-the-fence punches was more impressive. Who is right? As far as the Nevada State Athletic Commission is concerned, the outcome of the fight isn’t really worth investigating. But one judge in one round rendered a decision that is starkly in contrast with the numbers, and that is worth looking at. Perception is reality, and human perception is subjective and inherently flawed. Perhaps Trowbridge has never taken leg kicks personally, or perhaps the other judges look more for technical merit in fighter rather than ferocity. But as long as individual rounds can be evaluated in such drastically different ways, we’ll continue to see surprising and controversial decisions. It’s not to say the Trowbridge was wrong in his scoring, but that disagreement over round two supports efforts to establish better uniformity among how judges weight and evaluate fighting tactics in MMA. And until the NSAC offers greater visibility into their own internal quality control processes aimed at reducing variance in evaluating fights (assuming they have them), Dana White will continue to have just cause urging fighters never to leave it in the hands of the judges. “Fightnomics” the book is now available on Amazon! Follow along on Twitter for the latest UFC stats and MMA analysis, or on Facebook, if you prefer.