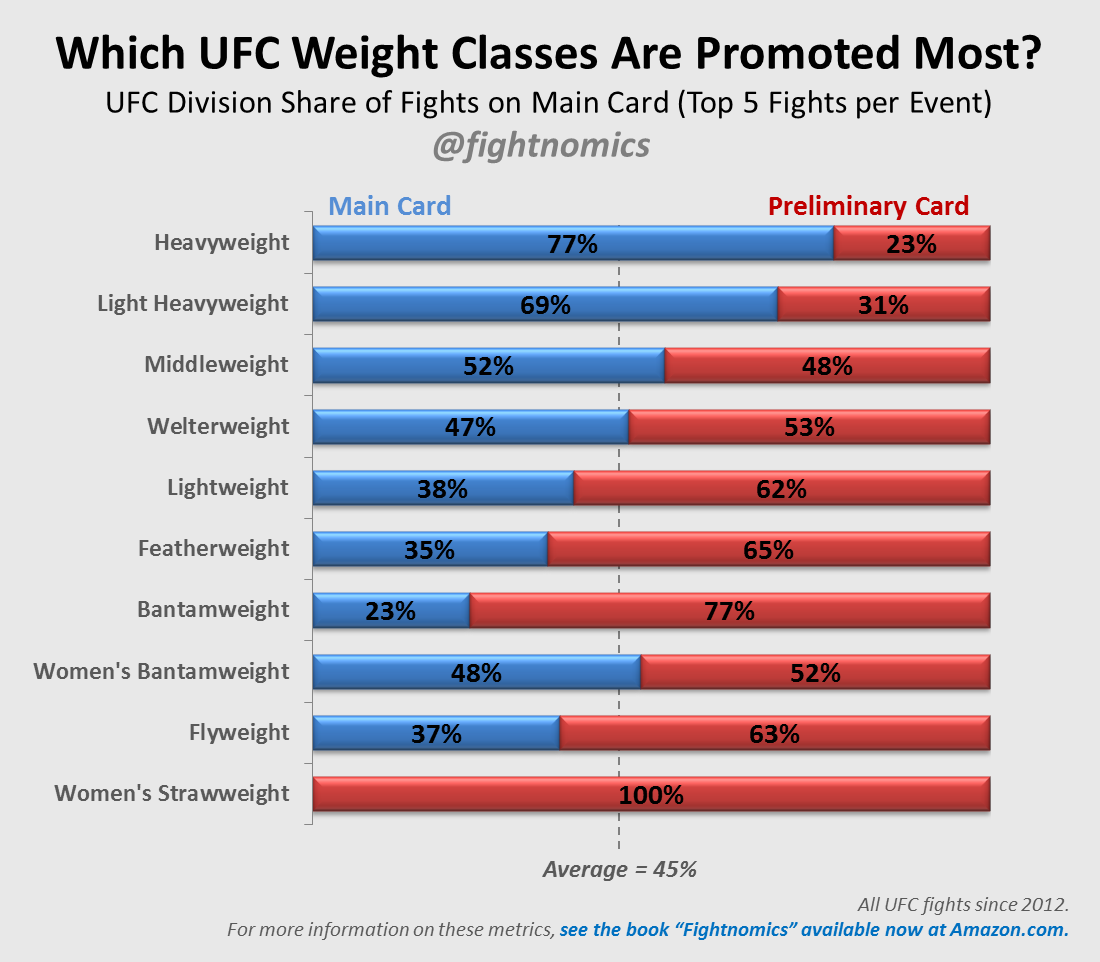

By Fightnomics We’ve heard that smaller guys get no respect, but is that really the case? Which weight classes are given highest billing, and who is more likely to appear on a main card relative to other divisions? Dana White recently suggested than when there are multiple titles on the line, the ordering of top billing defers to the larger division. Hence, Ronda Rousey has twice defended her title in the co-main event of the evening, followed by larger fighters in the evening’s finale. However, as recently as UFC 169, the Bantamweight title was held as the main event with the longer reigning champion of the larger Featherweight division defending a title in the co-main. That was likely due to the star power of Urijah Faber challenging for the Bantamweight strap, and the apparent lack of similar interest between 145 pound champion Jose Aldo and challenger Ricardo Lamas. Regardless of how the UFC chooses to promote events, there’s clearly some variation on the rules of thumb. But the macro-trends should reveal some good insight into how divisions are truly treated when it comes to promoting them on the big stage. Fighters in the Flyweight division claim size-bias, and recent media comments tend to agree. So that brings us back to the question at hand: Are the smallest fighters being under-promoted? The answer is, sort of. First let’s look at the share of each division’s fights that occur on the main card versus the preliminaries. The Main card in this case is the top five fights per event, which isn’t a perfectly consistent threshold, but it’s close enough.

For all the complaining, it’s definitely not the Flyweights who are seeing the fewest main cards. In fact, there are two other divisions, both larger, that see a higher share of fights airing on the prelims. The Flyweights compete in the top five fights of the night 35% of the time, while the Featherweights compete there 35%, and the Bantamweights just 23%. The Women’s Bantamweight division certainly has no grounds to complain with 48% of their fights on the main card, behind only the largest three divisions in the promotion. So the smaller guys are getting less respect, but not the Flyweights. It’s really the Bantamweights, and maybe even the Featherweights with cause for complaint. At least Ian McCall’s accusations of “small person-ism” are directionally accurate. The size-bias is also true historically, as it has been long noted in combat sports that fans prefer bigger fighters. The UFC didn’t even carry a roster below Welterweight for a time, and the new additions occurred slowly for smaller and smaller fighters over the years. The same is now true for women’s divisions. Heavyweights rarely end up on the prelims, competing below the top five fights just 23% of the time – the least of any division. Light Heavyweights aren’t far behind at 31%, and no other division is even close. The Welterweights are the closest to the break-even point, considering that in aggregate the top five fights make up 45% of fight cards during the period in question. The rest (except the Women’s Bantamweights) are below the average. And this isn’t trivial; these trends hit fighters right in the pocket book. Sponsor dollars have always been dependent on card placement. Heavyweight fighters already average more average base pay, but they also can earn more in sponsorship based on their frequent placement on the main card. But how about cutting the data another way, in terms of average card placement? Perhaps there’s a different trend among fighters on the main card or elsewhere.

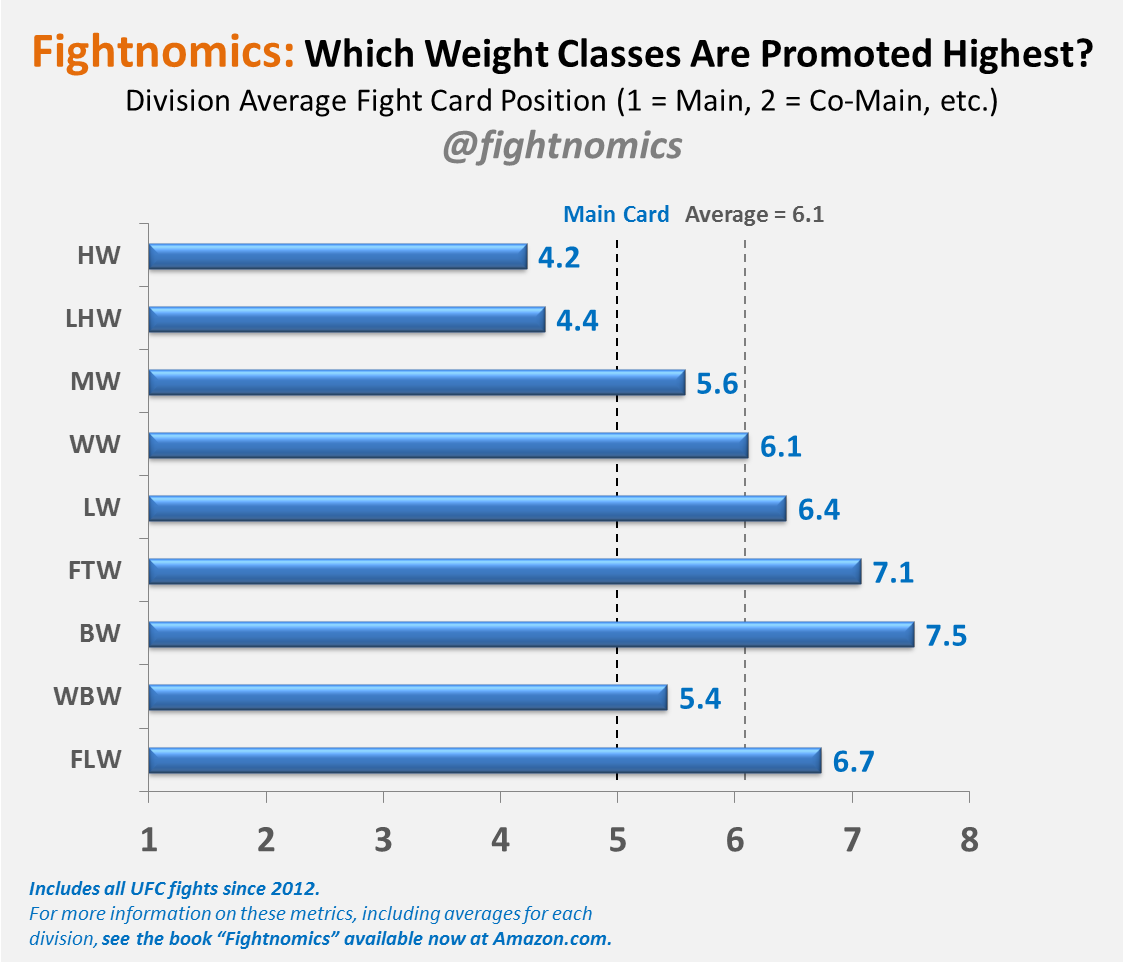

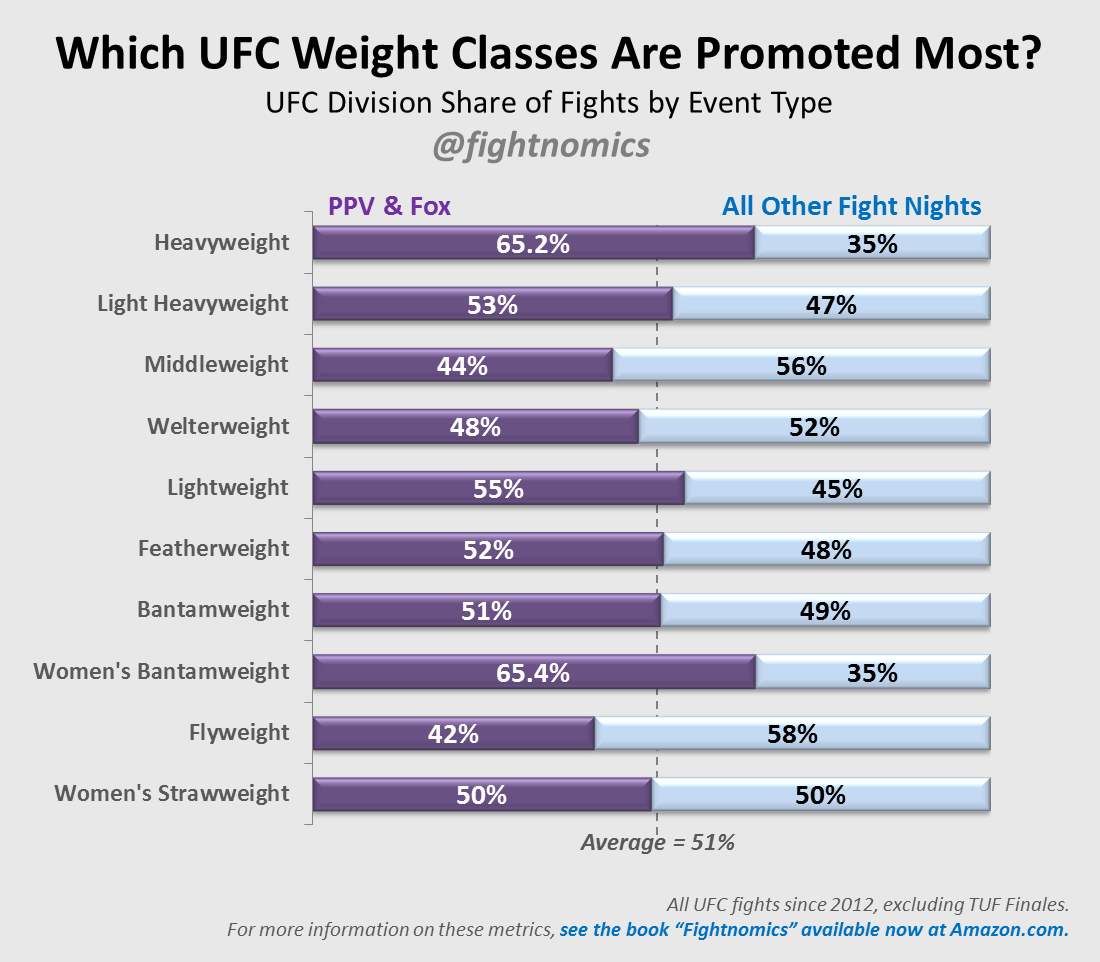

There’s definitely still a clear trend of larger fighters averaging a higher card position. But then the trend is thrown off by the last two divisions to be added to the UFC, the Women’s Bantamweights and the Flyweights, who buck the system and get promoted higher on the card on average. So are the small divisions complaining unjustly? Perhaps. And yet it’s the wrong small divisions that we’ve historically singled out. But there are a few more places to look. What if we take the most prestigious bookings as Pay-Per-View and Fox broadcasts, and then separate all other Fight Nights? Who enjoys the most spots on the UFC’s biggest stage?

Ah-ha! Gotcha. Those poor Flyweights only spend a paltry 42% of their fights on the real deal cards, and the majority on Fight Nights of lesser billing. But that’s just slightly below the Middleweights at 44%, which is hardly damning. This graph is perhaps even more remarkable in that the Women’s Bantamweight division slightly edges out the Heavyweights in the share of fights they spend on higher profile events. It was a close call, but the extra decimal shows the ladies getting the largest share of fights at events the UFC promotes the most. Meanwhile, the Flyweights get the least. So Ian McCall may be right after all. So what does it all mean? Even the last cut of the data could be misleading, as Fight Night cards arguably have larger viewership than many Pay-Per-View cards. I’ve excluded the TUF Finale events due to the fact that their weight classes selection is not as random. In terms of event prestige, the divisions are a lot closer together except for the largest men’s (and women’s) divisions getting preferred access. And more importantly, fighter pay, and even fighter bonuses no longer depend on the event you’re competing at. So while card placement may be a badge of respect, ultimately if you keep winning you’ll make more. If you’re an exciting and hyped fighter, then you’ll make a lot more. When it comes to hyping and promoting fights, long-standing MMA logic has been that fans love knockouts, and the big guys deliver them at the highest rates. But the claims that Flyweights get worse placement than other divisions is just plain not true. However, if anyone wants to complain, the Bantamweights could have a case. Find out more about MMA statistics, “Fightnomics” the book is now available on Amazon! Follow along on Twitter for the latest UFC stats and MMA analysis, or on Facebook if you prefer.