Last night (June 7, 2014) featured one of the most controversial judging decisions in the history of mixed martial arts following the co-main event of UFC Fight Night 42, as Diego Sanchez scored a split decision victory over Ross Pearson. This isn’t the first time Sanchez has scored a controversial decision, either, and considering he’s had 20 bouts thus far inside the Octagon, perhaps statistics can help us find an answer to the problem. Let’s delve right in: The Uber Tale of the Tape suggested that while Diego Sanchez loves to maintain a high pace and swing for the fences, he doesn’t land very often and his defense is terrible. This pattern has resulted in him getting battered and bloodied in numerous recent fights while rushing forward against more technical and patient strikers. Along comes Ross Pearson, a fighter who likes to stand and trade, and who has accuracy and defensive avoidance that are superior to those of Sanchez. The grappling scenarios, as expected, would be moot. Sanchez’s takedowns – while frequent – have some of the lowest success rates in the division. Meanwhile, Pearson’s takedown defense is well above average. If Pearson was willing to stand and trade with Sanchez, that’s what we were going to see. And of course, that’s what happened.

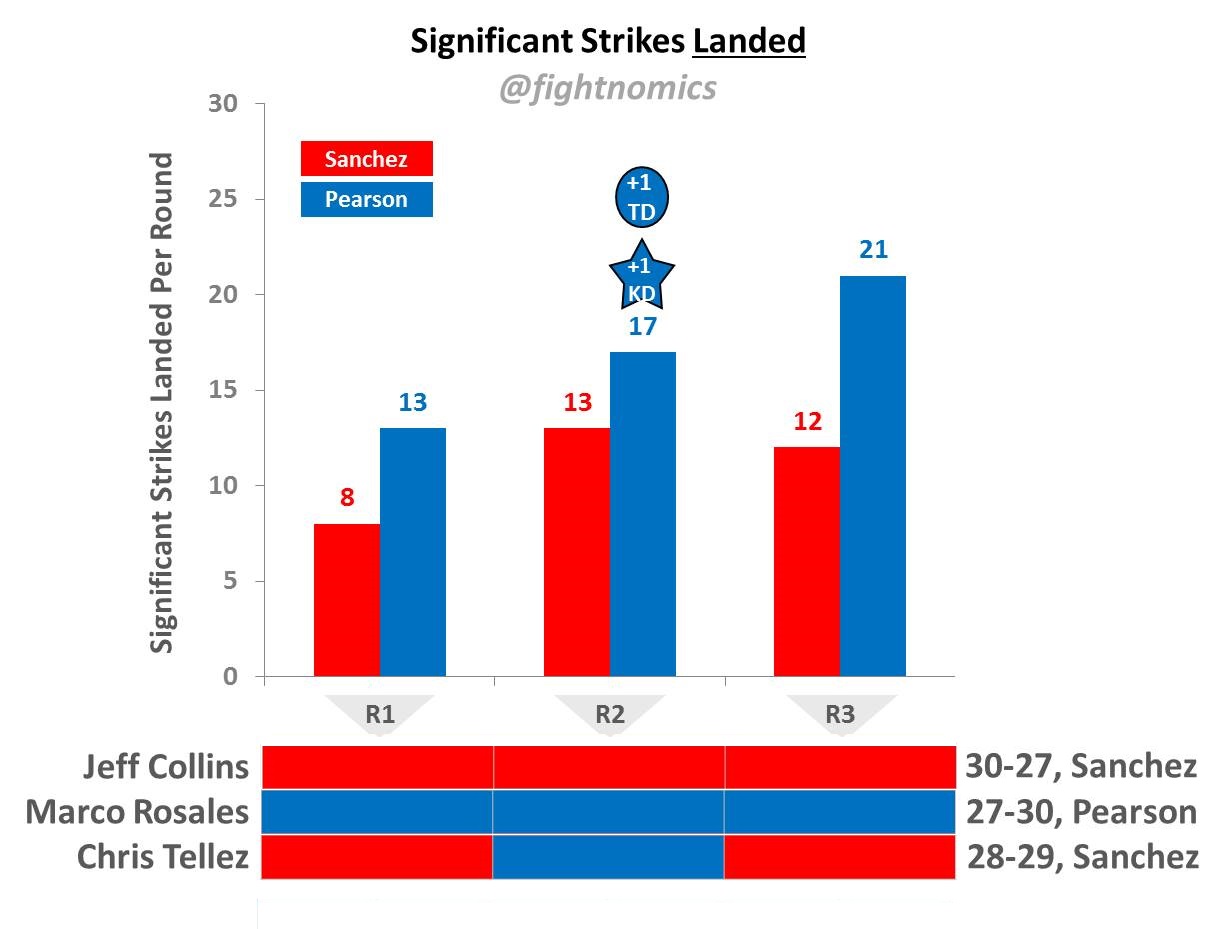

Round-by-round Sanchez pressed forward, often swinging wildly and missing. Round-by-round Pearson landed more strikes, and landed the harder ones, too. Round-by-round Pearson would avoid the occasional wild knee or takedown attempt, then shortly thereafter land a clean combo to punctuate Sanchez’s otherwise benign pursuit. Counters were thrown, most were landed, and at one point Pearson dropped Sanchez to nearly get the first in-round TKO stoppage of Sanchez in his 20-fight UFC career. It was close, but as usual, Sanchez survived. Despite going the distance, however, it was still clear that Pearson landed more strikes, the only takedown of the fight, and even scored an important knockdown. From an effectiveness standpoint, there was no question who did more damage – as the faces of the fighters plainly revealed. Sanchez was as battered and bloody as usual, while Pearson still looked pretty clean. In the end, the media and fans seemed in rare unanimous agreement in regards to the winner going to the post-fight commercial break. Then the scorecards were read. After two opposite 30-27 scores from the judges, the final 29-28 tipped the Split Decision to Sanchez. Twitter exploded. People were citing the round-by-round stats even before the scores were read, and even more so after. Headlines started hitting MMA media about one of the biggest “robberies” and “worst judging decisions ever.” I have to say that I agree with those sentiments in that the better fighter that night lost. That’s the most unfortunate part. But the question of how bad the decision was is a separate and more complex issue. First, here’s what the two fighters did in meaningful measures of effectiveness:

To fans and media scoring the fight, stat-keepers, and perhaps anyone other than Diego Sanchez and two of the judges that night, Ross Pearson was the better fighter without question, and arithmetically was superior in all ways. He landed more strikes, had a takedown, and even a knockdown. It was stochastic domination. There was no room here for trading off Sanchez’s takedowns to compensate for eating a few more strikes, or his submission attempts offsetting a knockdown. He was swept in all categories. So why score the fight for Sanchez in any round? The first answer anyone can give is “well, Sanchez came forward, so he got the edge in Cage Control.” The loose term “cage control” is still in the Unified Rules of MMA, and ultimately it leads to the most outrage by fans. It can often be summed up with a very simple, alternative view of the fight. Perception is not always reality. When you remember that judges are watching live, without commentary or replays, and that striking in MMA can happen awfully fast, here’s a more likely view of what the judges actually saw.

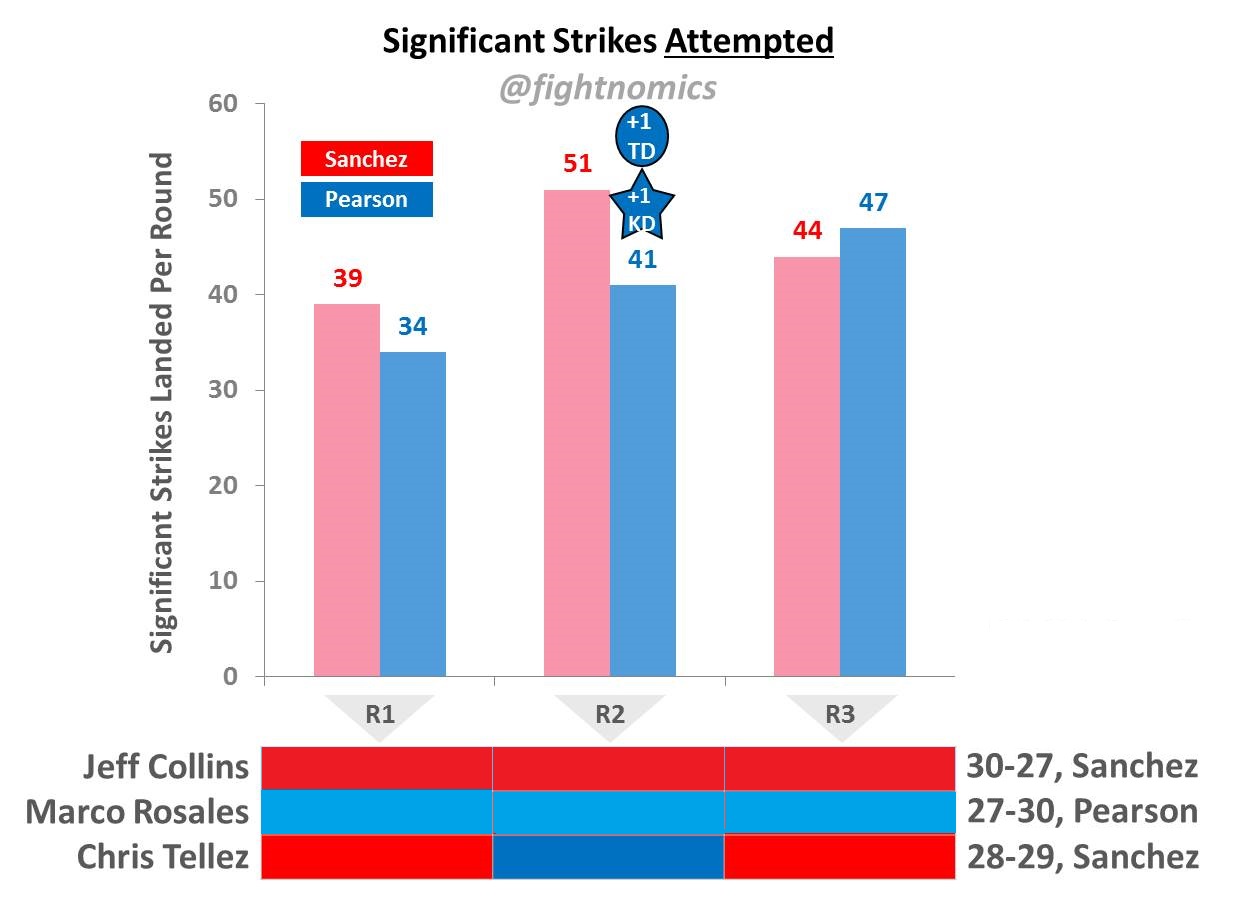

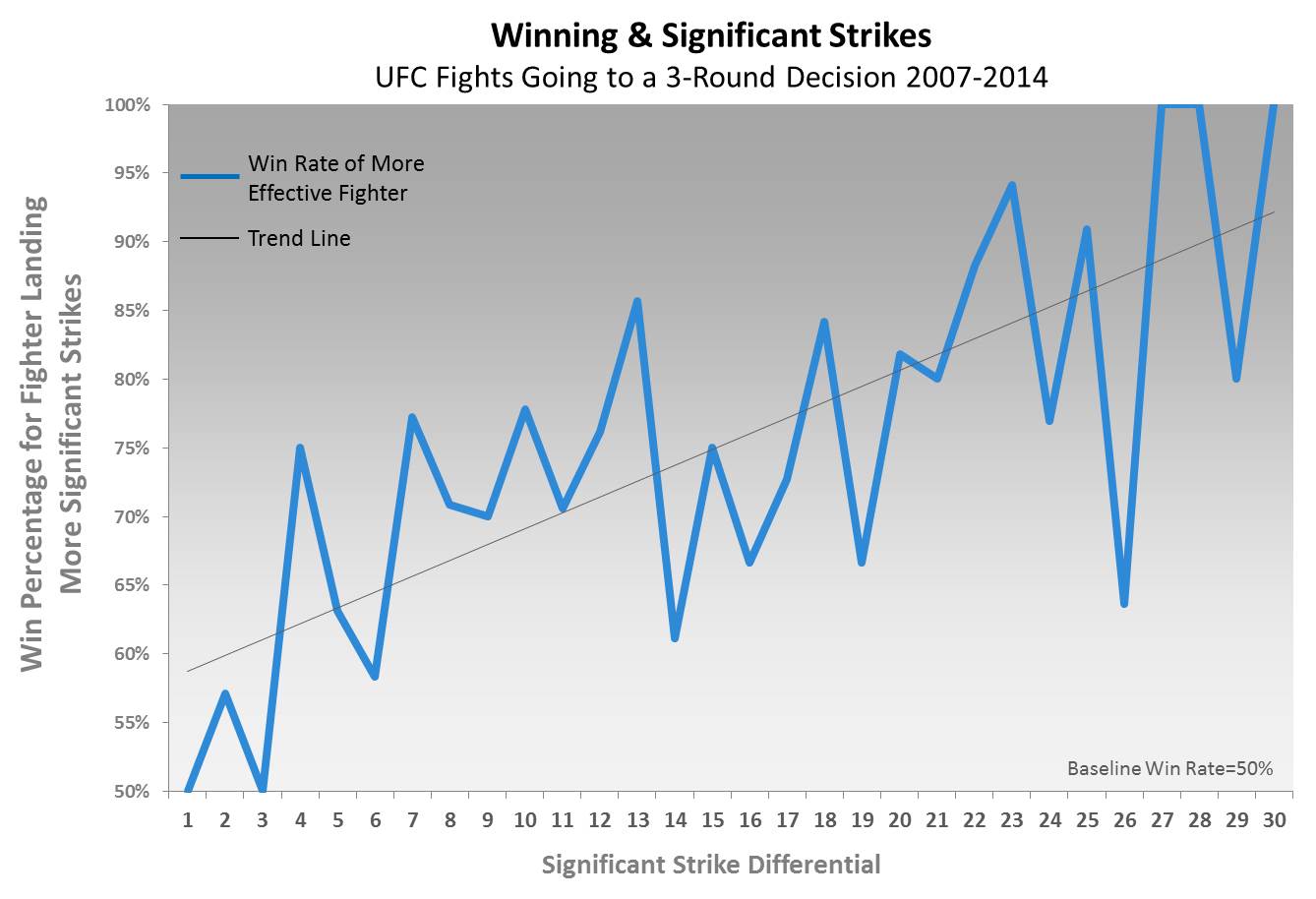

In this view of an MMA fight, fighters are evaluated on effort, not just effectiveness. It’s the attempts that matter, not just the landed strikes. Basically, missing still counts for something in the judge’s eyes. And because that something is greater than zero, it can have a measurable effect in certain situations. Like this one. Sanchez outworked Pearson in two out of three rounds, and the final round was the closest of all. Throughout the fight, Sanchez was the one walking forward and generally in hot pursuit making showy gesticulations, while Pearson was the one calmly backing up (while landing counters) and circling away. From a casual perception standpoint, Sanchez looked like the aggressor. From an effectiveness standpoint, Pearson picked apart a sloppy pursuer. Who should earn the decision? One would expect that trained, licensed MMA judges aren’t viewing the fight from a casual view. They are supposed to be identifying the more effective fighter. So how outrageous is it that Sanchez got the decision? Well, we can look back at fights that were predominantly standing (few takedown attempts, and very little time on the ground) and that went to a decision. Pearson’s 51-33 Significant Strike performance can then be compared to other fights where there was a differential in the same range. How did the guy who landed more strikes generally fare? So if we looked back at fights that went to a decision and the difference in Significant Strikes landed, we first see that this metric of output is highly reflective of who wins.

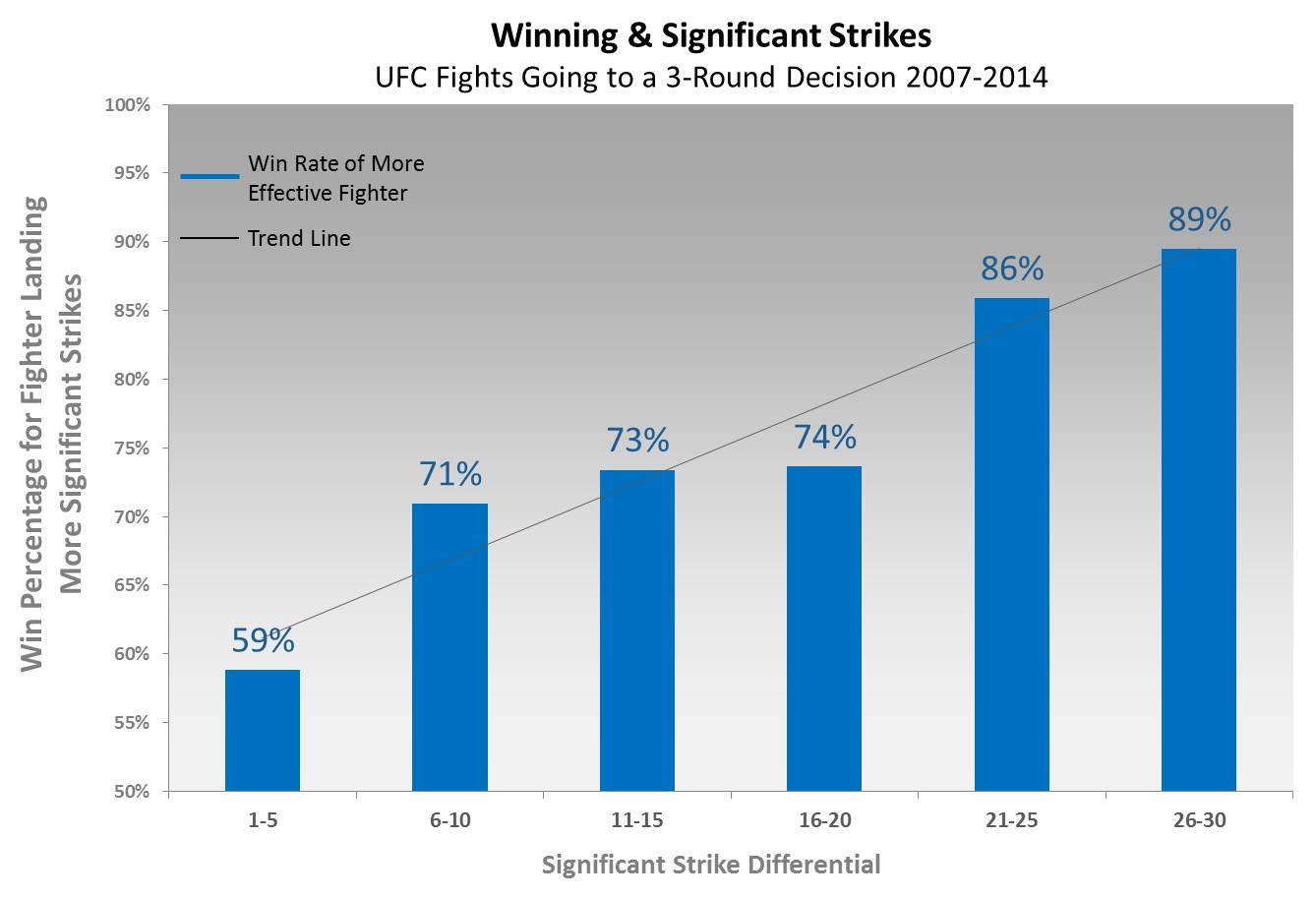

The fighter who lands more Significant Strikes generally wins, and the more he outlands his opponent, the more he wins. In Pearson’s case, he landed 18 more significant strikes than Sanchez, which on the trend line correlates with a 75% win rate. If that graph is too bumpy for you, let’s group the strikes into larger buckets.

Winning three out of four may make the outcome of Pearson-Sanchez a little easier to swallow, but remember that this macro-trend doesn’t account for other variables like takedowns and knockdowns. An even more nuanced analysis would examine the different types of strikes landed, because not all strikes are created equal. Power strikes, landed or missed, are more influential than jabs. And leg strikes aren’t as impressive as a kick to the body. The judges, whether they realize it or not, are looking at attempts (not just landed strikes) and also the target of the strikes. In Sanchez’s case, he threw a lot of missed strikes and a lot of body kicks, each of which do count for something in the judges’ eyes. That said a differential of 18 Significant Strikes landed is pretty steep. In fact, looking back through recent UFC history at fights where there was a differential of 15-20 Significant Strikes in a primarily standing contest (eliminates grappling variables), the more effective fighter won 91% of the time. Then lay on the lack of takedowns by Sanchez, and the Knockdown by Pearson, and this scenario starts looking like a pretty sure victory. But it’s not 100% sure. The fact that these numbers aren’t 100% reminds us of the volatility and uncertainty in MMA decisions. And even if we do see a win rate of 100% for a certain scenario, it doesn’t mean we won’t see the opposite happen next weekend. Looking back at the round stats from this fight, it’s clear that judge Jeff Collins had a bias towards Sanchez for whatever reason. The judge’s brain wasn’t necessarily looking for ways to score the fight for the Red corner, there may have been a preconceived preference for the value of cage control and volume, rather than effectiveness in scoring the rounds – as those were the only variables that favored Sanchez. However, in round three Pearson not only out-landed Sanchez, but even outworked him on attempts too. That just leaves aggression and cage control as the only possible variables that still favored Sanchez at that time. And yet, this particular variable in theory is supposed to be less important that actual effectiveness according to the “Rules of the Octagon.” Lastly, maybe, just maybe, we’re missing the most powerful force of all, one that Diego Sanchez and a sizable portion of the American public believes determines sport contests. The conclusion is that the decision was not as unexpected as it could have been simply because it was, after all, a human decision. That’s how we know it was flawed – a human was involved. One score was clearly skewed, even allowing for generous interpretation of aggression. But the disagreement between judges here is not as uncommon as we would think. It’s just a little more uncommon based on how the fight played out. It’s rare that a judge or referee is punished after a bad performance on the job, but boxing recently saw CJ Ross take a leave of absence from the Nevada State Athletic Commission after being on the “wrong” side of two hugely controversial and high-profile boxing decisions. Will we ever see the same thing in MMA? Who knows? The current commission system does not seem to (at least publicly) analyze the performances of judges to hold accountable those who misinterpret the rules or simply don’t understand fighting styles. We continue to see massive amounts of disagreement among judges who are watching the same two fighters compete in the same cage for just 15 minutes (for more details on this phenomenon, see Chapter 12 of the book “Fightnomics”). It doesn’t seem that complicated to know who won a fight, but when we remember the human factors involved in judging, the confusion is not so surprising.