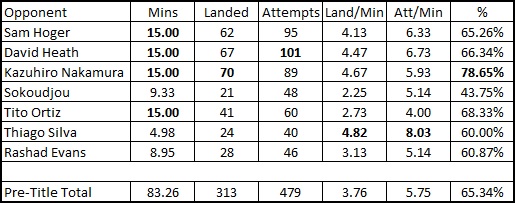

There have been two extremely disparate schools of thought coming out of Lyoto Machida’s unanimous decision victory over Gegard Mousasi at UFC Fight Night 36 this past Saturday night (Feb. 15, 2014). The first is that Machida is back to being the enthralling fighter he was early on in his career. Opponents couldn’t figure him out and he brought a variety of offense to the octagon that we had not seen before. It was remarkable to watch this man work, and hey, if his fights went 15 minutes that was no problem because it was just more time to watch him work. The other end of the spectrum is that Machida is back to being the boring, overly patient fighter he was early in his career. Sure, opponents couldn’t hit him, but that’s because he was constantly playing defense. How else could you explain a fighter who was clearly superior to his opposition not being able to finish? Early in his UFC career, I found myself in the first camp in regards to Machida. I enjoyed his fights, didn’t think he was all that conservative, and was amazed at the way he could set up strikes and use angles like no other fighter. Eventually, after the impressive knockouts of Thiago Silva and Rashad Evans, (because as we all know, finishes equate to worthwhile fights) Machida had won over the majority of MMA fans. While looking back on it now “The Machida Era” was ridiculous, but at the time many thought he had the chance to reign over the light heavyweight division for an extended period of time. As we know, Machida’s reign didn’t last long, but since becoming the champion back in 2009, he hasn’t had to battle the “boring” stigma that surrounded him early in his career. However, it’s my contention that the Lyoto Machida we see before us right now is the most boring iteration of the fighter that we’ve ever seen in the octagon. This has nothing to do with some of the mixed results Machida experienced late in his run at 205lbs, and it obviously looks past the fact that three of Machida’s last five victories have come via highlight reel knockout. From both an empirical and aesthetic standpoint, Machida’s output has waned drastically from his early UFC career. Not only that, but his efficiency has decreased as well, although this can likely be attributed to the increase in his level of competition. Let’s take a quick look at the arc of Machida’s career for a moment (let me take this time to preface the remainder of the article by saying that these numbers come from FightMetric. While I don’t always agree with the stats on the site, they are most accurate in the striking realm where the data requires the smallest amount of interpretation. Also, in an effort to get this examination out as quickly as possible I haven’t accounted for the amount of time Machida spent on the ground in these fights, working under the assumption that his bouts are primarily contested standing.) The Brazilian has spent a shade over 207 minutes inside the octagon across his 17 bouts with the organization. He has attempted 991 significant strikes across that time, and landed 526 of them. That’s an average of 4.79 significant strikes attempted per minute, and 2.54 landed. In the seven fights up to and including Machida’s title victory over Rashad Evans he attempted five or more significant strikes per minute (SSAPM) in all but one, his bout with Tito Ortiz which contained some prolonged periods of grappling. He also landed 60% of his strikes or higher in each of those seven bouts save for the UFC 79 battle against Rameau Thierry Sokoudjou. During this period, Machida posted averages of 5.75 SSAPM, 3.76 significant strikes landed per minute (SSLPM), and had a 65.34% connection rate on those strikes.

There have been two extremely disparate schools of thought coming out of Lyoto Machida’s unanimous decision victory over Gegard Mousasi at UFC Fight Night 36 this past Saturday night (Feb. 15, 2014). The first is that Machida is back to being the enthralling fighter he was early on in his career. Opponents couldn’t figure him out and he brought a variety of offense to the octagon that we had not seen before. It was remarkable to watch this man work, and hey, if his fights went 15 minutes that was no problem because it was just more time to watch him work. The other end of the spectrum is that Machida is back to being the boring, overly patient fighter he was early in his career. Sure, opponents couldn’t hit him, but that’s because he was constantly playing defense. How else could you explain a fighter who was clearly superior to his opposition not being able to finish? Early in his UFC career, I found myself in the first camp in regards to Machida. I enjoyed his fights, didn’t think he was all that conservative, and was amazed at the way he could set up strikes and use angles like no other fighter. Eventually, after the impressive knockouts of Thiago Silva and Rashad Evans, (because as we all know, finishes equate to worthwhile fights) Machida had won over the majority of MMA fans. While looking back on it now “The Machida Era” was ridiculous, but at the time many thought he had the chance to reign over the light heavyweight division for an extended period of time. As we know, Machida’s reign didn’t last long, but since becoming the champion back in 2009, he hasn’t had to battle the “boring” stigma that surrounded him early in his career. However, it’s my contention that the Lyoto Machida we see before us right now is the most boring iteration of the fighter that we’ve ever seen in the octagon. This has nothing to do with some of the mixed results Machida experienced late in his run at 205lbs, and it obviously looks past the fact that three of Machida’s last five victories have come via highlight reel knockout. From both an empirical and aesthetic standpoint, Machida’s output has waned drastically from his early UFC career. Not only that, but his efficiency has decreased as well, although this can likely be attributed to the increase in his level of competition. Let’s take a quick look at the arc of Machida’s career for a moment (let me take this time to preface the remainder of the article by saying that these numbers come from FightMetric. While I don’t always agree with the stats on the site, they are most accurate in the striking realm where the data requires the smallest amount of interpretation. Also, in an effort to get this examination out as quickly as possible I haven’t accounted for the amount of time Machida spent on the ground in these fights, working under the assumption that his bouts are primarily contested standing.) The Brazilian has spent a shade over 207 minutes inside the octagon across his 17 bouts with the organization. He has attempted 991 significant strikes across that time, and landed 526 of them. That’s an average of 4.79 significant strikes attempted per minute, and 2.54 landed. In the seven fights up to and including Machida’s title victory over Rashad Evans he attempted five or more significant strikes per minute (SSAPM) in all but one, his bout with Tito Ortiz which contained some prolonged periods of grappling. He also landed 60% of his strikes or higher in each of those seven bouts save for the UFC 79 battle against Rameau Thierry Sokoudjou. During this period, Machida posted averages of 5.75 SSAPM, 3.76 significant strikes landed per minute (SSLPM), and had a 65.34% connection rate on those strikes.

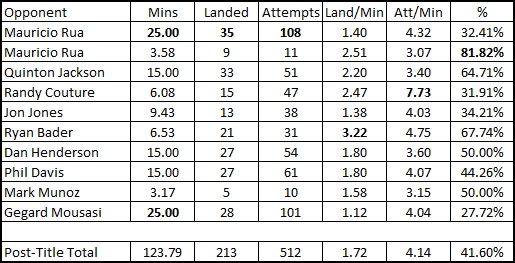

After he won the title however, all of Machida’s numbers have declined markedly. As I mentioned earlier, the reduction in the percentage of his strikes landed (and as a result, actual strikes landed) is easily explainable based on the fact that Machida has faced much tougher competition since winning the title than prior to. What this does not explain however is the fact that Machida’s output has waned considerably since UFC 98. The five SSAPM mark that we discussed Machida exceeding regularly prior to that has only happened once since, and that was against a nearly 48-year-old Randy Couture. In this set of 10 bouts, Machida’s SSAPM dropped from 5.75 all the way down to 4.14. That’s a decrease of 28%, or if you stretch a fight out over 25 minutes, the difference between attempting 144 strikes versus 104. Against Gegard Mousasi at UFC Fight Night 36, Machida attempted 101 significant strikes over 25 minutes in a bout that was contested almost entirely on the feet.

In my eyes, and according to the stats, early on in his UFC career Machida was a fighter who used creative angles and his unique skillset in order to create his own offense, and it was fun to watch. Whether it’s been the product of him being knocked out by “Shogun” to drop his title, or simply a more conservative approach adopted in an effort to retain his title, he’s no longer that same fighter. Now he relies on his opponent to create the openings for him, unless they are entirely outmatched (like Couture). Fighters know how talented Machida is and they’re hesitant to rush in on him because he’s still capable of producing a devastating knockout when they do (right, Ryan Bader?). My bigger issue is that Machida is still capable of creating offense on his own (as evidenced by the Munoz KO), but is increasingly less willing to do so. MMA opinions are often based on results rather than processes. It’s why Machida — despite regularly producing innovative offense — was incorrectly considered boring early in his career when he didn’t have a highlight reel to back him up. At the same time, it’s why some people are so indignant about that same label being attached to the current version of “The Dragon” when the numbers back it up. Even if you appreciate Machida’s feints, fakes, angles and everything else that he does in the cage, it means nothing if he refuses to actually throw strikes. Increasingly he’s been reticent to do so, and while some may praise how “tactical” that makes him as a fighter, I can’t help but see the fighter he was, the fighter he is, and the massive gap between the two in actual activity. Lyoto Machida is still a fighter that you have to watch because of the things he’s capable of when he sets his mind to creating some violence. That said, the 2014 version of him is hands down the most boring we’ve ever seen.