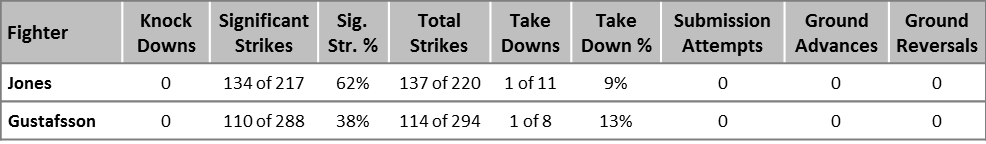

For some it was a controversial robbery of an improbable upset. To others it was a record-breaking title defense by one of the sport’s pound-for-pound best. Either way, the UFC 165 main event title fight between champion Jon Jones and challenger Alexander Gustafsson was an epic five-round war that is an immediate contender for Fight of the Year. To me, I also see a head-scratcher when I compare fighter performance to the judges’ score cards. A fight with so much on the line, and one that was so close, merits further examination due to the mild controversy surrounding the decision. Though I agree with the overall decision by the judges, I think there may be some hidden lessons in the data on how we actually evaluate fights versus how we should evaluate fights. Because the fight spent an overwhelming majority of the time in a distance striking position (as opposed to the clinch or on the ground), it simplifies things and allows us to look at just the distance striking stats and still have a pretty good picture of how the fight went down. Each fighter landed one takedown, but the fight did not stay on the ground for long, so this really is a striking-only affair. The only non-Significant Strikes were jabs that occurred during the brief clinching between the fighters, and these too were minimal (Jones totaled 3, Gustafsson totaled 5). Everything else was thrown in a traditional distance striking stance. Going into the fight the historical performance data on Gustafsson showed that he was a high-paced headhunter. Gustafsson averages 11.1 significant strikes per minute, well above the benchmark for UFC fighters and especially light heavyweights. In past fights almost 90% of his total standing strikes have been aimed at the heads of opponents, which is also way higher than the UFC average. His overall accuracy is about average in most metrics, but low for Significant Striking accuracy (because most of his strikes are low-success head strikes). His defensive striking metrics are poor, though his chin has held up well. So all in all we should expect an active, albeit slightly sloppy striker that presses the action with traditional head strikes. Jones on the other hand, tends to use a more controlled pace at 7.5 attempts per minute (though still slightly higher than average) and has higher strike accuracy, especially in overall Significant Strikes. His higher accuracy is partially a testament to his mix of striking, which is far more diverse than most fighters. While standing, 64% of his strikes are thrown at the head, which is well below the 81% benchmark. That’s because in prior fights he mixed in 15% aimed at the body, and 21% aimed at the legs. While this reduces his overall threat of knocking someone out, it can still obviously be an effective plan to attack opponents all over their body, all over the cage, and also strategically to set up more damaging blows. Knowing all that, here’s how the fight went down by the FightMetric Box Score.

What’s interesting is that the box score reveals that both fighters really stuck to their historical patterns in this fight. Gustafsson was far more active in attempts, but Jones still managed to land more strikes thanks to much higher success rates. What’s not shown is target selection, but further analysis reveals that Gustafsson relied more heavily on typical boxing strikes aimed at the head while Jones, as usual, attacked all over with a diverse mix of strikes and target selection. Both fighters actually were a little more diverse in their target selection than usual, but Jones was definitely more active in leg and body strikes. Both maintained a higher than average pace, which helped fuel the fight as such an exciting bout. So that all makes sense, but what exactly were the judges tracking when they recorded their scores. At the end of the fight, judges gave Jones the win with scores of 49-46, 48-47, and 48-47. Close one for sure, but still a unanimous decision victory for the champ. How did they reach their conclusions? Let’s refresh ourselves with the official scoring criteria that the UFC employs, and then look closer at the stats from the fight to see if we can decode how the judges were scoring each round. Section 14 (Judging), Sub-Section B: Evaluations shall be made…giving the most weight in scoring to effective striking, effective grappling, control of the fighting area and effective aggressiveness and defense. Ok. So in the following order of priority, we should consider: (1) Effective striking, for which Significant Strikes landed is the best metric. (2) Effective grappling includes takedowns, dominant positions and submissions. It ends up being a wash here for the most part except for a bump in Gustafsson’s favor in R1 and another bump to Jones in R5. No other ground stats were recorded. (3) Cage control is harder to gauge with statistics (at least now), and must be done visually, but a proxy could be who was attempting more strikes and takedowns. (4) Effective aggressiveness and defense can factor in who was attempting more strikes compared to who was more accurate. If one fighter attempted more strikes that might be construed as “effective aggressiveness.” On the other hand, if Fighter A was much more accurate, then Fighter B probably had less “effective defense.” Significant Strikes We’ll look at this fight in several ways. First, let’s just consider who landed more Significant Strikes throughout the fight. In a fight where there were essentially no grappling techniques employed, isn’t this what it boils down to? Who landed more of strikes that weren’t just taps in the clinch?

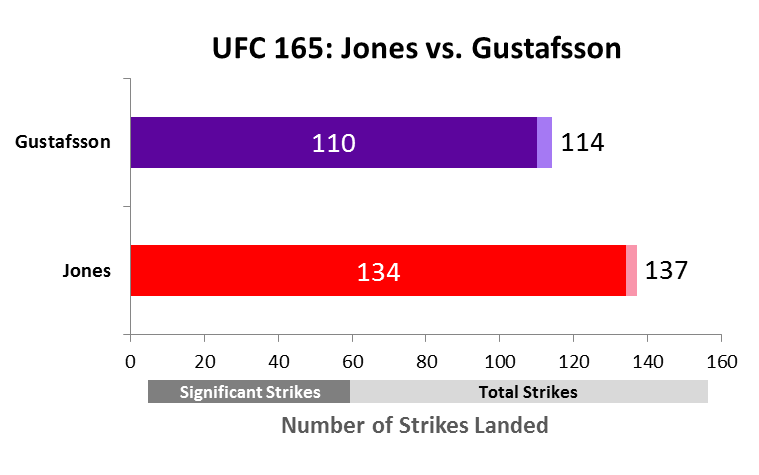

The macro-view shows it was Jones who landed more strikes than Gustafsson. In this very simplistic view of the fight, Jones deserves the nod in a close match, which is exactly what happened. But that’s not how fights are judged. Each round, judges were required to score that round in isolation of the rest of the rounds. In theory, this also implies that each round has equal value so that clearly winning a round is worth more than barely winning a round (10-8 rounds ignored here due to their rarity). Whether this is the best system of judging is another headache altogether, so we’ll stick to the situation at hand. Round by Round Effectiveness Let’s just look more closely at the round by round stats to understand what the judges might have been looking at when they filled out their cards, as well as each judges corresponding round winner.

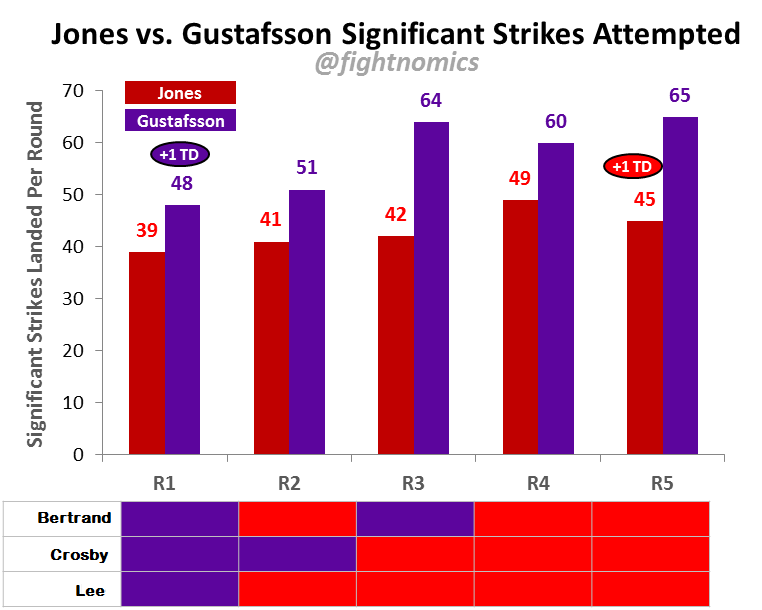

If we just look at who landed Significant Strikes more often (remember, there were very, very few non-Significant Strikes, or any other tangible metrics) on a round by round basis it certainly looks like Jones should have won the majority (if not all) of the rounds. What’s strange, however, is that when you look at the judges’ scoring the most skewed rounds towards Jones’s performance were the ones mostly likely to be scored for Gustafsson on the cards. On strikes landed alone, the closest two rounds (4 and 5) were the only ones where Jones swept the cards. So what’s the disconnect? Let’s consider three other legitimate factors, and one not so legitimate one. We’ve already covered the first scoring criteria of effective striking, and Jones is the clear winner both overall, as well as in a round by round comparison. However, this measurement doesn’t explain why Jones lost Round 1 across the board, or why some judges didn’t give him Rounds 2 and 3. For Round 1, we could surmise that judges credited the takedown as making up for some of the difference in landed strikes. This falls into category (2). In Rounds 2 and 3, however, Gustafsson did not land any more takedowns, yet he still won each round on one of the judges’ cards. It could also be argued that the takedown in Round 1 didn’t last long, and Gustafsson had literally no offensive moves at all: no strikes landed or attempted on the ground, no submission attempts, and no position advances. Should that have really overcome the difference in landed strikes? The shock of seeing Jones get dumped on his back for the first time in his UFC career (however briefly) was likely not lost, even on the judges. So despite being outlanded in strikes by Jones, that takedown for Gustafsson probably counted for something, and might have been enough to carry the round. Now that takedowns are out of the way, let’s also consider two more subtle factors further down the scoring criteria list. Round 1 saw very visible damage done to Jones’ face thanks to a glancing blow that sliced open Jones’ brow, which bled profusely for the rest of the fight. Judges are human and we’re very aware when we see blood. The damage done by striking is definitely a factor in determining who won a round, even more so when things are close. This could add credit to Gustafsson’s “effective aggressiveness,” or debit Jones’ “effective defense,” or both. The damage done might also add a little “effectiveness” to Gustafsson’s striking measured in category one, such that despite fewer landed strikes, they were somehow “worth more” than Jones’. Another potential factor is “cage control,” technically (3) on the scoring criteria list. Cage control is credited to whichever fighter tends to dictate the position in the cage. Just picture which fighter was moving forward rather than backward, or which fighter is closer to the center of the cage rather than closer to the perimeter fence to figure out who had cage control. In an otherwise evenly matched standup striking affair, cage control can be a differentiator. This one is fairly subjective for a fight like this, as both fighters were clearly willing to engage. Despite the volleys of punches Gustafsson threw, Jones fired numerous kicks back, and even surged at the end of the round. Hard to imagine that this factor would trump others with higher priority in that round. Even if it there was a clear difference in cage control from round to round, would that trump the other, more important criteria of effective striking? The last factor is also fairly subjective, effective aggressiveness and defense, and here’s a critical insight from the FightMetric database. Historically, when a fight is close judges tend to lean the way of the more active fighter, not necessarily the fighter who landed more strikes. Think about it. Judges are watching live and real-time, and during a rapid exchange, it’s nearly impossible to tell who landed the cleaner shots. They don’t get slow motion replays, and they certainly don’t get statistics. After the dust has settled each round, judges will likely credit the fighter who was simply more active. That’s not consistent with the order of criteria from the official scoring guidelines, but it’s the reality of human judging. It suggests that we look at strike attempts, rather than strikes landed. Round by Round Activity Let’s re-examine the round by round stats, this time looking at Significant Strike Attempts, rather than just those that landed.

When we aligned these stats with the judging scores, again there’s some inconsistency. Gustafsson was the more active striker in all rounds. Yet the closest round in terms of attempts was the first, the only one he carried unanimously on the cards. Round 3 saw the biggest differential in Gustafsson’s activity, and yet he only won on one card. Lastly, despite landing the closest number of strikes to Jones in Rounds 4 and 5 with the highest pace of activity, these were the two that unanimously went the other way. Clearly, activity is not what the judges were scoring in this fight. What gives? That leaves me believing there was a final, invisible force at work in the judge’s section that night: bias. Bias is ubiquitous whenever humans are involved, so I do not use that term as an insult. It exists everywhere, and isn’t necessarily intentional or malicious. It’s just that our perception of reality isn’t perfect because our brain has a variety of invisible biases at work, influencing everything we perceive, all the time. Even my own vast research into the subjects of psychological and cognitive biases leaves me with my own bias that bias was at work here. Follow? Therefore, and I could be off here due to my own bias, but the research into human judges and referees in other sports would support my conclusion that bias is probably a part of MMA judging whether we like it or not. It is completely reasonable to believe that the initial shock of Gustafsson – a huge underdog coming into the fight – performing so competitively early on was enough to cause judges to credit his performance with a winning round. After that initial rush had worn off, however, judges were then swayed back to Jones by his methodical and stout performance, as well as the need to counter-balance their initial scores for Gustafsson in the hopes that one would differentiate at the end. Ultimately, bias in a high profile fight like this that is competed so closely will tend to favor the favorite – usually the incumbent champion – simply due to the unspoken desire not to be the source of controversy. Sure, there are plenty of examples of underdogs winning the cards in a close fight, and boxing is famously rife with them at the moment, but in the long-run judges and referees are less likely to intervene when the stakes are so high and the world is watching. The sin omission of non-calls of fouls in the closing minutes of a close basketball game, or calling a ball on a close strike when the count is 2-0 in baseball are well documented patterns elsewhere in the sports world that support bias at work. Without a little bias, sport isn’t really human. Opposing fans will watch the exact same players play the exact same game, and yet completely disagree on who played fair, what should have been a penalty or a score, and who deserved to win. That is part of what makes sports so passion-inducing, and failure so tolerable. As sure as superstition, bias will likely never disappear from the human race. In this case, whatever weighting we give to the various scoring criteria, there appears to be inconsistencies in their use from round to round based on objective evaluation of the statistics. If judges performed their roles perfectly and objectively, whatever value they assigned landed strikes versus attempts should have been maintained throughout the fight, and either Gustafsson should have carried more rounds later on, or Jones should have won more up front. This did not happen. Whatever swayed the judges early on for Gustafsson (perhaps blood, perhaps a single fleeting takedown, perhaps the sheer volume of his strikes), was not enough to sway them later on, despite the most important aspects of his game still being intact. At the end of the day we are left with a few interesting takeaways from all this. First, the numbers show differences in how the fighters fought, but those differences were very consistent with their historical performance patterns. That’s interesting in and of itself, as it supports the analysis of historical performance in advance of upcoming fights. Whew! The overall result was also consistent with what the numbers suggested about their striking tendencies: a closely fought, very exciting fight. A related takeaway is that having two high-activity fighters who both like to control the cage can usually lead to an exciting fight. I’m also reminded of recent examples like Dustin Poirier versus Erich Koch, and Brad Picket versus Michael McDonald. Second, the judges seemed to have used a sliding scale of scoring criteria that initially favored Gustafsson’s style, but quickly swayed back towards Jones. It wasn’t likely intentional, but statistics for scoring performance show little difference from round to round to warrant such differences in scoring. What’s left is subjective interpretation and biased perception, which isn’t really what judges are supposed to be doing. Lastly, there’s the simple conclusion that MMA is still a fight, and sometimes fights are just close and hard to judge. Trying to decode the judges’ scores may not make sense, and therefore there is further reason to explore reevaluating the scoring criteria so that everyone, especially the fighters, know what wins a round. Finally, for the gamblers out there, getting into the sometimes irrational “heads” of the judges may pay off when it comes time to pull the trigger on live betting. @fightnomics