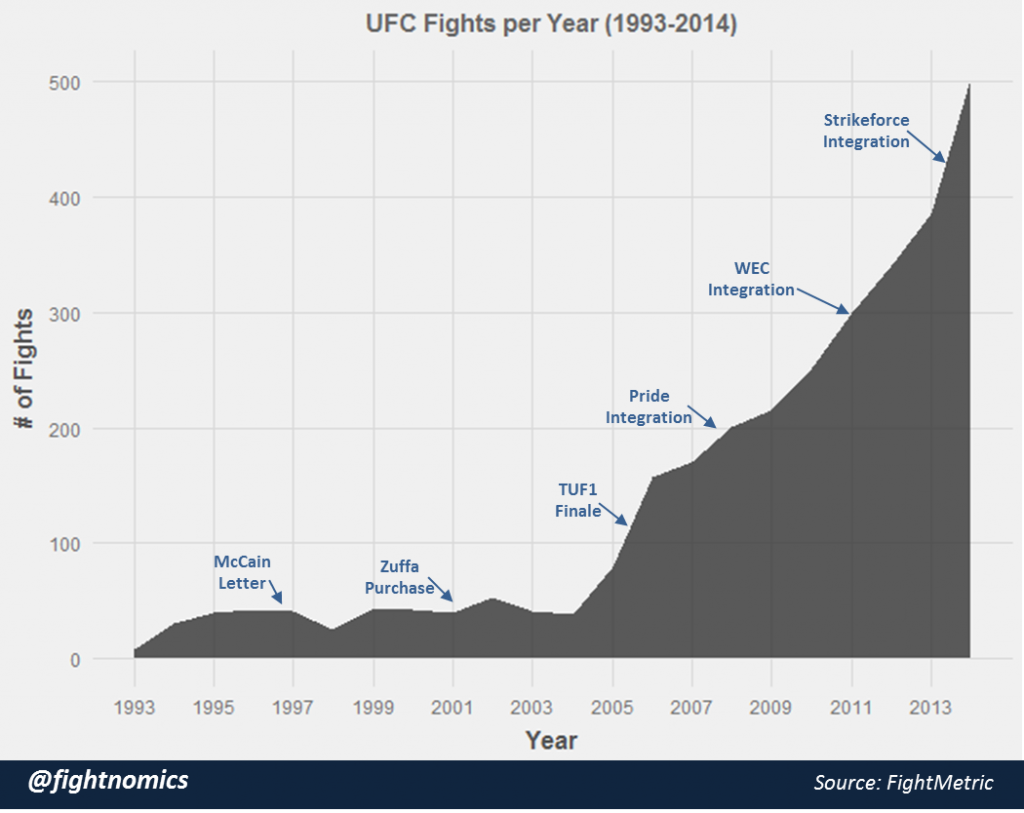

By @fightnomics Some argue that the peak of UFC popularity was around 2005. It was heyday of the “Iceman” Chuck Liddell and the “Pitbull” Andrei Arlovski. Half of all fights that year ended in a knockout, and another quarter of all fights ended in submission. Decisions made up less than a quarter of all fights, and the epic barnburner between Stephan Bonnar and Forrest Griffin at The Ultimate Fighter Season 1 Finale tipped the unconvinced into devoted fans. And the UFC delivered when demand began to surge. Whereas just 39 fights occurred in 2004, the annual fight count more than quadrupled to 158 in 2006. It was the fastest period of growth in the promotion’s history, and the period of time that shoved an underground sport into the eyeballs of mainstream awareness. Here’s the total fight UFC count annually through 2014, which totals 3,056 fights.  The dark years of the sport began with the letter from John McCain to US Governors pleading them not to sanction “human cockfighting” in their states. The UFC limped along on the cusp of extinction through the Zuffa acquisition in 2001. It would take several years before the rapid period of growth that pre-dated, and magnified by the success of the Ultimate Fighter. But obviously, despite the unprecedented volume of events in 2006, the UFC wasn’t done growing. In addition to sustained organic growth, Zuffa also made a series of strategic acquisitions that expanded the star power in their roster, and created entirely new divisions. Now with the growth phase potentially tapering as the schedule reaches a saturation point, 2015 should bring the least amount of growth in total fight count that the UFC has seen in over a decade. That stability will mark a new phase for the promotion that has had its share of growing pains along the way. Zuffa 3.0 will still manage to promote over 500 fights annually, but over more diverse geographies, and under more strict regulation than ever before. And that’s probably a good thing. Tightening the reins on the product and streamlining the operation for long-term survival is something that seemed forgotten during the wild ride of the 2000’s. And while domestic markets may be saturated, there’s plenty of appetite for more first-class MMA abroad. But despite the growth phase just now stabilizing, we can still learn something about “how” fights went down in the UFC, and not just how often. Here’s another look at the same chart, this time with the method of fight ending differentiated.

The dark years of the sport began with the letter from John McCain to US Governors pleading them not to sanction “human cockfighting” in their states. The UFC limped along on the cusp of extinction through the Zuffa acquisition in 2001. It would take several years before the rapid period of growth that pre-dated, and magnified by the success of the Ultimate Fighter. But obviously, despite the unprecedented volume of events in 2006, the UFC wasn’t done growing. In addition to sustained organic growth, Zuffa also made a series of strategic acquisitions that expanded the star power in their roster, and created entirely new divisions. Now with the growth phase potentially tapering as the schedule reaches a saturation point, 2015 should bring the least amount of growth in total fight count that the UFC has seen in over a decade. That stability will mark a new phase for the promotion that has had its share of growing pains along the way. Zuffa 3.0 will still manage to promote over 500 fights annually, but over more diverse geographies, and under more strict regulation than ever before. And that’s probably a good thing. Tightening the reins on the product and streamlining the operation for long-term survival is something that seemed forgotten during the wild ride of the 2000’s. And while domestic markets may be saturated, there’s plenty of appetite for more first-class MMA abroad. But despite the growth phase just now stabilizing, we can still learn something about “how” fights went down in the UFC, and not just how often. Here’s another look at the same chart, this time with the method of fight ending differentiated.

The early years saw a 100% finish rate in fights, because every fight continued until one fighter stopped the other by T/KO or Submission. In 1995 judges were implemented for the first time, so decisions were possible in addition to finishes. Still, most fights ended before going to the score cards, partially due to the early inconsistent skill in the sport, and the stylistic mismatches that frequently occurred. Fast forward to the peak years of growth and still most fights were being finished. It wasn’t until 2006 that the finish rate trend changed substantially. The maturing sport was starting to stabilize. What happened then was also a slow migration of average weight in the UFC ever downward, as new weight classes kept popping up underneath each other. This allowed smaller fighters to enter UFC competition, and also led larger fighters to cut more weight to fight in more competitive divisions. But the chart showing the raw number of fights is hard to eye ball when it comes to how fights ended. So here’s one last look at the same data, this time shown proportionally for each year, so each type of fight ending method is charted as a proportion of that year’s total, such that each year adds up to 100%.

The biggest macro trend is that the overall finish rate is declining. As mentioned, this is due to a number of factors working together (and occasionally against each other). Not only was the sport becoming more mature and competitive, but the average size of fighters was declining significantly. While smaller fighters doesn’t always mean fewer finishes (there appears to be a floor on finish rates), a modern UFC with a large group of Flyweights, Bantamweights, and Featherweights looked very different from the years when all fighters weighed in at 170 pounds or higher, and knockouts occurred nearly half the time. But the other big trend is the recent period of stability in fight-ending methods. Both Submission and T/KO rates have stabilized. And this occurred during the addition of new women’s divisions. While 2015 will be revealing in a number of ways, we probably shouldn’t expect any drastic changes from the last few years. As a general rule of thumb, about half of UFC fights will end inside the distance, while half will go to a decision. And of those going to the cards for a decision, a quarter of those will be split or majority decisions. Hope you enjoyed this very brief history of UFC fights. Stay tuned for more angles on all sorts of historical trends in the sport. For information on getting the “Fightnomics” the book, go here.